Teton Endurance Traverses

Fight or Flight Traverse (FA 2016)

Grand Traverse in a Day with Lewis Smirl (PR 19 hrs)

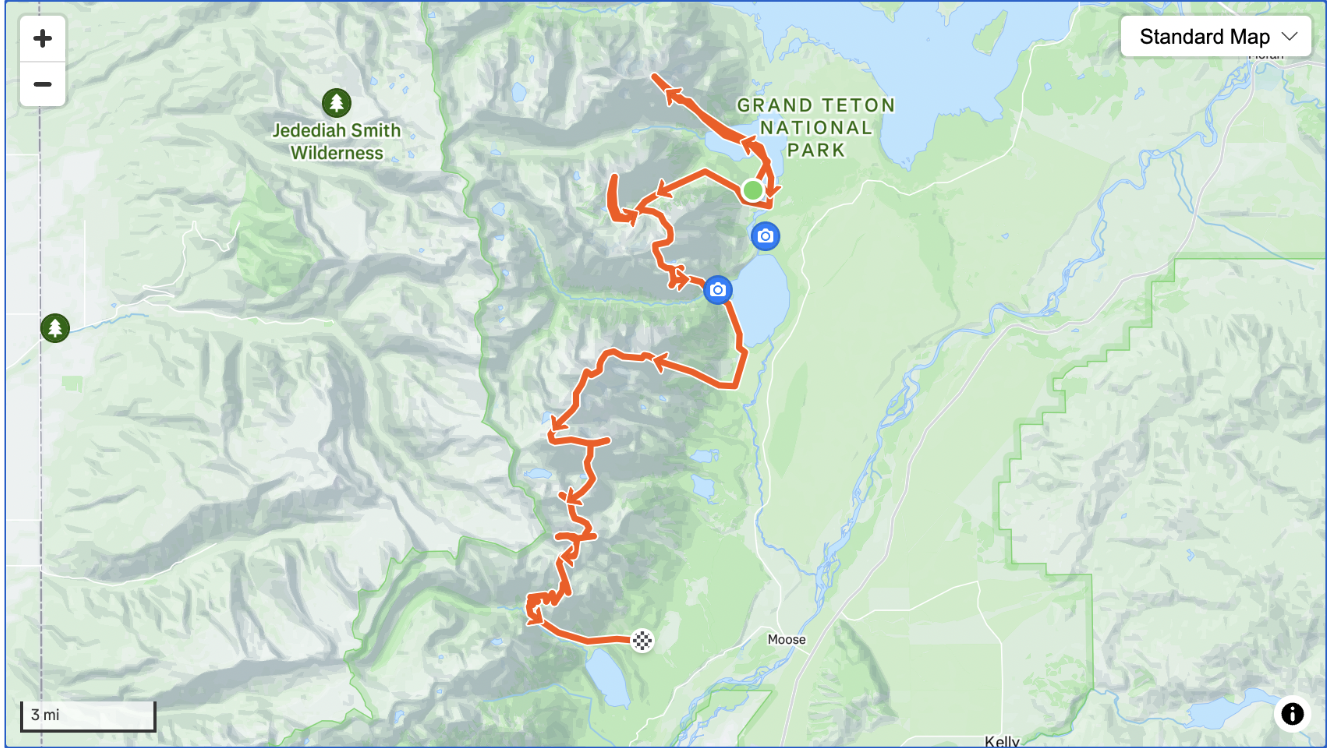

Fight or Flight Traverse:

A seven day tour of the Teton Range from north to south, summiting 50 peaks, over 102 miles and 122,000 feet of vert gain and loss. Click on Image for Strava link to Approximate Route

Traverse Background: After completing the Perception Traverse, which runs from Mount Moran to Albright Peak, the next logical step was to extend it on both ends—creating a complete traverse of the entire Teton Range. At first, it felt like an overly ambitious goal, but after a few reconnaissance missions into corners of the park I had never explored, the dots began to connect. The traverse isn’t overly technical; I would only need a rope and partner for the Cathedral Traverse of Teewinot, Mount Owen, and the North Ridge of the Grand Teton. Still, I knew the endless scree-filled gullies and massive vertical gain and loss would make for a serious challenge.

The motivation to finally give it a try didn’t come until a full year after the death of my good friend and mountaineering mentor, Jarad Spackman, who had been killed in an avalanche the previous spring. I wanted to accomplish something that would have made him proud. Honoring him through this traverse felt like the best way to stay connected and to process the loss. I carried some of his ashes with me and spread them on every major peak. The Tetons were his playground, and he had inspired me endlessly to push my limits in the mountains.

Headed up Teewinot Mtn on Day Four of Traverse

Jarad was an accomplished snowboard mountaineer, logging multiple first descents in the Tetons, while climbing prolifically throughout the range and beyond. The name of the traverse is, in many ways, a tribute to his spirit—he was always the first to tie in and give something a try. He remained calm and composed in precarious situations, and in many ways, he was the man I always aspired to become. I loved him for everything he ignited in me. He was a great friend and a priceless mentor.

For me, this traverse will always stand as the pinnacle of my mountaineering career. It represents years of patience and the slow assembly of countless puzzle pieces. When it was finally complete, it felt as though I had explored so many hidden corners of my home range. Now, when I look up at the Teton skyline, I feel a deep sense of pride knowing I’ve experienced the entire horizon in one continuous effort.

This traverse is my tribute—to the Tetons themselves, and to Jarad. They are forever intertwined in my mind, and I hope this journey reflects the profound respect and gratitude I hold for them both.

Traverse Itinerary

Day One: East Face of Peak 10,333, Marmot Point, Ranger Peak, Peak 11,300, Peak 11,200, Doane Peak, Anniversary Peak, Eagles Rest

Day Two: Bivouac Peak, South Summit Mt. Moran, North Summit Mt. Moran, Drizzlepuss

Day Three: Mt. Woodring, Rockchuck Peak, Mt. St. John, Symmetry Spire, Ice Point, Storm Point.

Day Four: Teewinot, Peak 11,660, East Prong, Mt. Owen, Grand Teton (north ridge), Enclosure,

Day Five: Middle Teton, South Teton, Ice cream Cone, Gilkeys Tower, Spaulding Peak, Unnamed Blob, Cloudveil, Nez Perce

Day Six: Mt. Wister, Peak 10,696, Buck Mtn, Static Peak, Albright Peak

Day Seven: Prospectors Peak, Peak 10,989, Peak, 10,200, Mt. Hunt, Peak 10,425, Cody Peak, No Name Peak, Rendezvous Peak, Peak 10,400, Peak 9815, Peak 9734, Great White Hump, Mt. Glory.

Teewinot Summit: Day Four

Route notes: The hardest part of this route isn’t the technical climbing—it’s having the grit to keep going day after day. Most competent mountaineers could complete any single section of the route within a day, but the cumulative grind of covering so many miles over slow, uneven terrain is what makes this traverse truly difficult.

A solid seven-day weather window is essential, though often hard to coordinate. I completed the traverse during the third week of August, which typically offers the best chance for the Cathedral Traverse to be ice-free. In preparation, I found it helpful to put in several big days in the Tetons beforehand to get my ankles used to the constant impact and uneven footing.

While there are countless beautiful moments along the way, you should also be ready for long stretches of scree and loose terrain. Knowing each section of the route helps tremendously, though it isn’t strictly necessary. Before my attempt, I scouted every area rated 5.4 and above, and I’d recommend others do the same—it increases both speed and confidence. When fatigue sets in, it’s easy to drift off route.

I truly hope someone feels inspired to make a second ascent of this traverse. Experiencing the full sweep of the Teton Range in such an intimate way is one of the greatest gifts a mountaineer could hope for.

The Fight or Flight Traverse was featured in Men’s Journal Magazine and the Wyofile publication.

Many thanks to Crista Valentino for partnering on the Grand Traverse section, wouldn’t have succeeded without you!

Northern Section of Flight of Flight Traverse: peaks south of Buck Mtn not included.

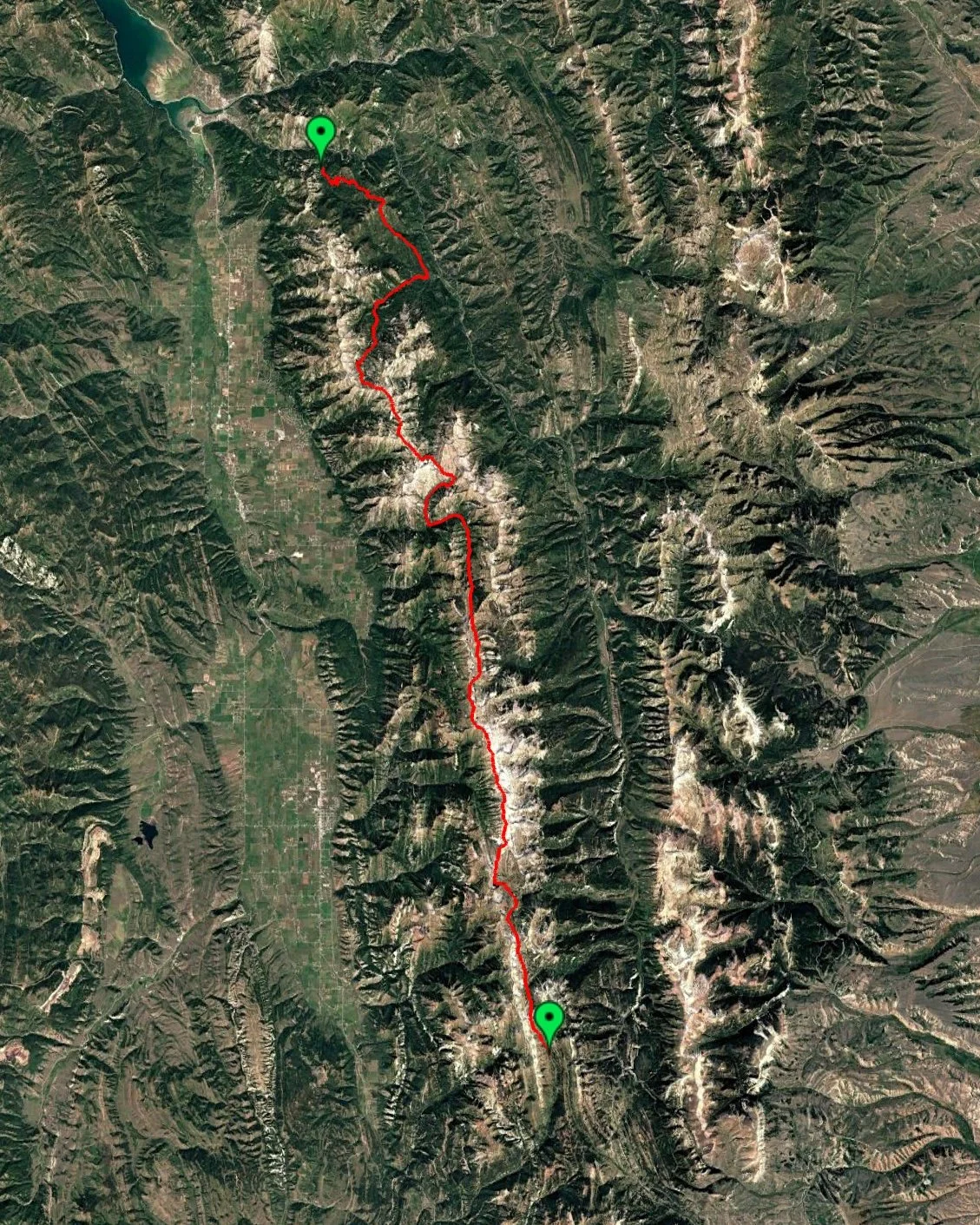

Windwalker Traverse

A 15 day traverse of the Wind River Range along the continental divide, summiting 50 peaks over 126,000 feet of vert gain and loss.

Click on Image for Strava link to Approximate Route.

Traverse Background: After finishing the Fight or Flight Traverse in 2017, I started looking to other ranges that might offer a similar experience. I had heard through the grapevive that Szu-ting Yi and Dave Anderson were going to attempt a North-South traverse of the Wind River Range along its central spine and it spiked my interest. I contacted the pair about joining their attempt, but understandably, they declined, having never met me before and with the start date rapidly approaching. Later that Fall I read about their attempt in Alpinist Magazine, although they stopped short of their ultimate goal due to weather, it was an inspiring journey. I then contacted the pair to see if the were likely to go for another attempt, they replied they were not. I then asked if it was acceptable to them if I gave it a go. They were receptive to the idea and wished me luck.

During that same summer, I had also started dating my future wife Elise Sterck, who is always up for an adventure. Amazingly, with only two months of compatibility data to pull from, she agreed to attempt the 15 day traverse with no signs of hesitancy. Truth be told, neither of us truly knew what we were in for, but both of us looked forward to the time together. With the car shuttle complete, we started our adventure at Union pass and made our way towards Downs Mountain. The first two days went splendidly, but the second night turned brutal. Setting up camp at 13,000 feet with turbulent winds, turned into a sleepless night with Elise vomiting, due to dehydration, on repeat for hours. Due to the strong winds, our tent poles were rendered ineffective, so we just wrapped the tent lining around our shivering bodies as we awaited daybreak. Once sunlight arrived, we checked the forecast only to find heavy snow was predicted for the upcoming day. Our luck running out fast, we descended below tree line within striking distance of our next objective, Gannett Peak. That night we curled up in our sleeping bags and settled in for 48 hours of swapping skeptical eye glances as we wondered what we had gotten ourselves into. On outward appearances, this easily could have turned into the lowlight of the trip, but in all actuality it created a strong foundation for our future lives together, as we learned about our mutual tolerance of discomfort and our penchant for staying optimistic in trying times.

Elise Sterck: Flagstone Peak-Day 2

Surprisingly, we woke up the following day to bluebird skies and an easy ascent of Gannett Peak, the highest mountain in Wyoming. Of course, the foot of fresh snow made for some wet sneakers, but it also provided us with some spectacular views and the most memorable day of our traverse. Having wasted almost two days waiting out the storm, we were worried our food supplies wouldn’t last us to our next resupply. However, with some rationing and quick steps we made it to our cache in Indian Basin without too much turmoil.

Continuing onward, we trudged through the central part of our traverse making easy non-technical ascents of many summits along the continental divide, seeing the core of the Wind River Range that most people miss out on. Upon reflection, it was during this time wandering on the high plateaus where our relationship fell into place. Discussing the twist and turns of our prior lives and imagining what might come next, felt safe and satisfying, like putting down a heavy backpack after a long day. During this stretch of the traverse, we decided to move in together and to take the following year off to travel the world climbing. I remember feeling such immense gratitude that we had found each other in such a big world. This time together confirming the simple truth, that all we needed to be happy in the future was just the presence of the other.

Gannett Peak-Day 4

When we finally reached the Cirque of the Towers, we were feeling tired but confident as the end was in sight. Little did we know, the roped climbing portion of our trip would be harder than expected. Weighed down with overnight gear and our bodies starting to deteriorate after eleven days of arduous travel, the Cirque Traverse zapped our last reservoirs of resilience. I had done this 15 peak traverse in one long day before, so I believed splitting it into two days would be a breeze. However, a fall at the crux late on the first day, severely effected my confidence, as I was left dangling on a few small gear placements, contemplating my mistake, one thousand feet above the valley floor. After this blunder, we changed tactics and hauled our heavy bags, over the problematic roof, but it slowed our pace down dramatically. After finishing a few sketchy rappels, where the anchor nuts wiggled out of their placements with ease, we found ourselves ascending the last steep ice and dirt gully at nightfall, barely holding on to our sanity as we navigated the last three hundred feet of disintegrating chaos.

Reaching the lip of the gully was a sublime experience and we were greeted with calm skies and a perfect two person bivy spot that served as our resting place for the night. I have never felt so grateful to be done a day of climbing, realizing that I was not only happy for my own survival, but more pleased that Elise, who has quickly becoming my life partner, had made it through the day as well.

Gannett Peak: Gooseneck Pinnacle-Day 4

The rest of traverse felt like a blur as we kept slowly summiting peaks and making our way to the end of the traverse. After two weeks of repetitive motion, Elises calf had developed an over-use injury and the threat of cutting our traverse short, just shy of the finish line, was a real possibility. I remember thinking that stopping would be unfortunate, but I was still leaving this trip with the best possible outcome, a committed partner who would sign up for this type of debauchery. However, Elise persevered as she always does and we summited the 50th peak under blue skies. Thinking our adventure was complete we descended below tree line with thoughts of fast food filing our minds, only to come face to face with a mama grizzly bear and her three cubs, most likely the most dangerous moment of the entire traverse. With both parties caught off guard, it could have turned ugly, but the female bruin backed away slowly and we went our separate ways, all limbs in tact.

Overall, we finished the traverse 15 days after we started, hobbling the last few miles to the trails end and celebrating that night with a hearty serving of burger and fries at the Lander Bar. By the end, our bodies were tired. the relationship had strengthened, and we couldn’t stop smiling.

Peaks Traversed

1) Union Peak. 11) Peak 12705 22) Peak 11584 33)Peak 12468 44)Warbonnet

2) Peak 11507 12) Pedastal Peak 23) Europe Peak 34) Mount Washaki. 45) Mitchell

3)Three Waters Peak 13) Flagstone Peak 24)Peak 11778 35) Peak 11925 46) Big Sandy

4) Shale Mountain 14) Gannett Peak 25) Peak 12230 36) Wolfs Head 47) Peak 11593

5) Peak 12399 15) Miriam Peak. 26) Halls Peak 37) Overhanging 48) Peak 12105

6) Peak 12302 16) Dinwoody Peak. 27) Odyssey Peak 38) Sharks Nose 49) Nystrom Peak

7) Peak 12254 17) Fremont Peak 28)Kagevah Peak 39) Block Tower. 50) Peak 12103

8) Downs Mountain 18) Angel Peak 29) Walt Bailey Peak. 40) Watch Tower

9) Peak 12702 19) Peak 11286 30) Tower Peak 41) Pylon Peak

10) Yukon Peak 20) Peak 11615 31) Mt. Hooker 42)Warrior 1

11) Peak 12705 21) Peak 11580 32) Peak 11886 43) Warrior 2

Block Tower: Last climbing peak of Cirque Traverse-Day 12

Traverse Notes:

Start: Union Pass (Seven Lakes Rd. with six days worth of food: ice axe/crampons) End: Sweetwater Gap Trailhead

Food/Gear Caches: Indian Basin (Five days worth of food) and Cirque to The Towers (trad rack, harness, shoes-4 days worth of food)

Protection: Small trad rack for cirque of the towers: Ice axe crampons for Gannett Peak

The Windwalker Traverse was featured in the Buckrail Publication.

Perception Traverse

Traverse Notes: This was my first legitimate foray into Teton epics. I’d done long runs before and summited plenty of peaks, but I had never completed an objective that added anything to the larger community conversation. Looking back, it was an audacious goal. I’d climbed each of the individual mountains involved, but I’d never linked them together—beyond the Cathedral Traverse.

I was at that precarious age where I had something to prove but no real accomplishments to back up my ego. I remember seeing Jimmy Chin at the climbing gym that year and thinking, “He looks human. If he can do epic shit, why can’t I?” Not the wisest motivation, in hindsight, but it got me dreaming about possibilities.

Before living in Jackson, I had only read about standout athletes in Outside magazine. But seeing them in real life ignites something inside you. When your neighbor—who happens to be a professional skier—runs your same pace, or you see the athlete you idolized growing up drunk at the bar, you start realizing the distance between “them” and “you” isn’t as vast as you were led to believe.

I knew I couldn’t compete with them in their specializations, but I wondered: if I focused on my strength—moving fast on moderate technical terrain—where might that take me?

Dreaming Bigger

In the Northern part of the Teton Range-Pic by Mike Azevedo

The Perception Traverse was my first attempt to test a theory: accomplished athletes are just like us—they just try harder. As long as I was willing to fail, and the safety margins seemed big enough, why not give it a shot?

The Grand Traverse was already the crown jewel of Teton objectives. But what about the peaks on either end—Moran to the north, Wister to the south? Why not extend the Grand Traverse, doubling the summits and vertical gain, while still tracing the same aesthetic skyline? That’s how the idea was born: link the front spine of the range, from Moran to Albright, touching most of the big pointy ones in between.

Day 1 — Water, Rock, and Doubt

The first day was huge: four peaks over 11,000 feet, three of which weren’t connected by a ridge, plus three subpeaks and a kayak across Leigh Lake.

I launched from String Lake at 2 a.m. in the only boat I owned—a beat-up $50 whitewater kayak I’d bought from a friend. Halfway across the lake, my legs started getting wet. I’d forgotten to replace the drain plug. Realizing I wasn’t going to sink was a relief, but it didn’t inspire confidence that the day would go smoothly.

Then I promptly climbed the wrong rock weakness above the CMC camp. Another fixable problem, but by then I was questioning my competence. Morning light brought renewed clarity, and I managed to summit Moran and descend to Mt. Woodring without incident. I even took a shaky selfie mid-run, thinking I was big shit. Truth was, I hadn’t done much yet—just fallen victim to early Instagram ego inflation.

By the time I hit Ice Point after Symmetry Spire, fatigue had set in. The tiny subpeak’s five feet of knife-edge exposure almost broke me. Soloing is a pure art form of self-expression, but without a partner, your only safety system is your mind—and mine was getting sloppy. I remember the internal debate: “No one will know if I turn around here.” But I would know. When you say you did something, you need to actually believe it.

That mindset got me to the top. I tagged the summit and made it down safely, ending day one utterly spent but oddly content.

Day 2 — The Cathedral

I met my partner, Taylor Luneau, at Lupine Meadows in the early morning, and we started up Teewinot. The light was perfect; the route finding, less so. Teewinot has claimed many lives for good reason—every step upward lures you into more dangerous terrain. Even though we’d both climbed it before, we found ourselves too far right and wisely turned around before over committing. Three women had died that same summer on nearly the same line. It hit home how fast things can unravel, no matter your experience.

Pic taken by Taylor Luneau on Day 2 coming down from Middle Teton

Once back on track, the Cathedral Traverse unfolded like a dream. The only real adversity was our overconfidence—thinking we could complete the Grand Traverse in a single day. We reached the top of the Middle Teton before calling it and spent a long, grumpy descent into Garnet Canyon trying to locate the bivy gear I had stashed. Taylor probably wanted to strangle me. Still, he rallied the next morning, and we pushed on retracing our steps back up to the col between Middle and South Teton.

Reaching the summit of Nez Perce and completing the Grand Traverse section of the objective together was pure joy. Our smiles in those photos still capture something irreplaceable—the wild, unrepeatable euphoria of a first big success.

Day 3 — Storms and Perspective

After finishing the Grand Traverse, Taylor headed home. I continued solo toward Wister, planning to sleep near Lake Taminah. I found a decent bivy spot just in time for one of the fiercest thunderstorms I’ve ever seen. Lightning ripped the sky apart, rain poured sideways, and I was safe—miraculously—under a rock overhang.

Moments like that reveal the paradox of the mountains: they make you feel both immense and insignificant at the same time. Big, because you’re connected to everything around you. Small, because you realize just how little control you actually have.

Day 4 — The Long Slog

Taylor Luneau and I on Nez Perce Summit after finishing the Grand Traverse section.

The next morning dawned clear. I scrambled up Wister, then endured some of the worst choss of my life descending to Peak 10,696 and on to Buck Mountain. That section is less “technical climb” and more “suffer-fest with views.”

By the time I topped out on Mt. Albright, I was deliriously happy. Not happy like “Instagram highlight reel” happy—more like “soul finally exhaling” happy. Four days of effort had stripped away my insecurities. For the first time, I felt like I’d earned my place out there.

Reflections

After two decades in Jackson, I’ve seen enough grief to avoid chasing pure danger. These days, I prefer horizontal risk to vertical risk—going farther, not harder. I still solo sometimes, but only when there’s enough margin to self-correct.

I have no illusion about being an alpinist. I don’t want to flirt with death; I just want to wave at it from a respectful distance and say, “Thanks for the reminder.”

For me, endurance in the mountains is a meditation—a way to test limits without courting oblivion. The Perception Traverse wasn’t just an experiment in physical endurance; it was my first real lesson in perspective.

Traverse Itinerary:

Day One: Mt. Moran (CMC route), Woodring Peak (SouthEast Ridge), Rockchuck Peak (East Face), Mt. St. John (North Ridge), Symmetry Spire (North Couloir), Ice Point (NW ridge), Storm Point (NW Ridge)

Day Two: Teewinot (East Face), Peak 11.840 (East Ridge), East Prong (East Ridge), Mt. Owen (Koven Route), Grand Teton (North Ridge), Enclosure, Middle Teton (North Ridge)

Day Three: South Teton (NW ridge), Ice Cream Cone (West Ridge), Gilkey Tower West Ridge), Spalding Peak (West Ridge), Cloudveil Peak (West Ridge), Nez Perce (NW couloirs)

Day Four: Wister Peak (NE face), Peak 10,696 , Buck Mountain (East Face), Static Peak, Albright Peak.\

Traverse Notes: It’s mostly fifth class scrambling, but unless your into soloing 5.8 terrain on the North Ridge of the Grand with alot exposure, you’ll need at least a 60 meter rope and a single rack. There are some great blogs about completing the Grand Traverse, including this one by Rolando Garibotti It’s the beta I followed and is spot on, Rolando is a legend and once held the speed traverse of the Grand Traverse in around 6.5 hours, holy mind bending stuff.

Salt River Range Traverse

3.5 day traverse along the Salt River Range in Alpine Wy. Approximately 55 miles the majority of which is above 9,000 feet. Strava link.

After more than a decade of wandering around the Teton and Wind River Ranges, my wife Elise and I had ticked off most of the moderate climbs that once kept us busy. With familiar objectives running thin, we started eyeing the lesser-known subsidiary ranges nearby, hoping to find something new that might still feel like an adventure.

The Salt River Range sits directly south of Alpine, Wyoming, and is only about an hour’s drive from Jackson, yet it remains largely ignored by tourists and many locals. The common perception is that it’s a place dominated by ATVs and hunters. That reputation may not be entirely undeserved, but after a few exploratory day trips we discovered something else entirely: a beautiful, remote range with real alpine character. You get none of the Tetons’ crowds, but all the rewards of scenic ridgelines and abundant wildlife, making it well worth a visit.

In early summer of 2025, Elise stumbled across a blog post by Forrest and Amy McCarthy describing a four-day traverse that tagged most of the major peaks of the Salt River Range from south to north. With a long weekend coming up and our list of Teton objectives shrinking, we thought, why not? In my mind, this would be a pleasant weekend exploring a new range, casually strolling along ridgelines and soaking in the novelty. That vision turned out to be only partially accurate.

It was a great adventure into an unfamiliar range, but those “pleasant ridgelines,” while undeniably beautiful, were also steep, loose, and relentlessly scree-filled. A phrase that became a refrain throughout the trip was, “How in the hell did Amy and Forrest do this in three days?”

That feeling of being gently catfished by a cheerful blog post hit hardest on day two, when we reached Mount Fitzpatrick, the highest peak in the range. The day before, we had started late in the afternoon leading into the Fourth of July weekend. The first five miles followed well-packed trails, eventually guiding us to a serene mountain lake where we spent our first night. Lulled into complacency, we convinced ourselves we had discovered the Shangri-La of multi-day traverses in the greater Yellowstone area. Stunning views, no people, and an entire mountain range seemingly reserved just for us.

A mile or two of this scree made us question our sanity for signing up for a such an unknown objective

In our minds, we were superheroes claiming our rightful bounty. Confident it was all in the bag, we slept in and enjoyed a leisurely breakfast, savoring the sounds of nature as we prepared for what we assumed would be an easy jaunt along the spine of a hidden gem. When we stepped off trail to climb Mount Fitzpatrick, spirits were high. We chatted about European destinations and which quaint Swiss town we might retire to someday, intoxicated by the possibilities that come with a new range and open horizons.

That optimism evaporated quickly. Descending the highest peak, we found ourselves swallowed by a sea of scree and jagged ridges. The mood shifted abruptly, and our sole objective became escaping the loose rubble and reaching the next plateau. The scree seemed endless, and as it dragged on, we began quietly questioning what exactly we had signed up for.

Eventually, the terrain eased briefly somewhere before Rock Lake Peak, granting us a short-lived reprieve. Adjusting our expectations and schedule, we started mapping out the days ahead, which suddenly looked far more ominous than they had the night before. The views continued to improve, but the scree returned with stubborn regularity at nearly every new ridgeline. Late on day two, just when we thought we might finally be past the worst of it, we found ourselves caught high on the ridge in an electrical storm. Distracted by photos and dulled by fatigue, we hadn’t noticed the clouds building until retreat became urgent.

Heart rates spiking, we scrambled along the ridge until we could descend toward safety, eventually slipping down a steep and slippery slope to a nearby lake. Given the early July timing, we assumed finding open water at elevation would require a significant descent. Instead, we discovered that while most lakes above 9,000 feet were still frozen, one had a small opening that allowed us to refill water. It felt like a minor miracle.

Somewhere past Mt. Fitzpatrick contemplating what might come next.

Day three began with sore legs and foggy minds. We opted to stay off the ridges for a while, contouring toward the col south of Cabin Lake Peak. Even at lower elevations, the terrain offered plenty of surprises: thawing north-facing headwalls, abandoned snowmobiles, and conditions that felt far more like spring than midsummer. Spirits remained decent, but predicting what lay ahead felt almost hallucinatory. With so little prior experience in the range, it was hard to read the landscape or anticipate what the next hour would bring.

The remainder of day three unfolded slowly but enjoyably. We regained the ridge west of Man Peak and carefully worked our way north toward Mount Stewart. Just before making camp, we nearly committed to a major descent to avoid an especially precarious ridgeline, but with patience and methodical movement, we found a way through.

Elise North of Rock Lake Peak right before the thunderstorms hit

On day four, we woke high on the ridge and began preparing for the final push of the traverse. Elise’s shins were flaring up badly, and it was shaping up to be our hardest day yet. The steep scree was as ever-present as it had been since day two, and by the time we reached Prater Mountain, Elise’s body was in full revolt. At that point, we faced a choice: continue along the ridgeline into unknown scree purgatory or drop down toward Murphy Creek Trailhead and bypass the mountain altogether.

With dwindling supplies, only half a day of sunlight left, and battered bodies, we turned downhill, deviating from Amy and Forrest’s high alpine line. Even so, we still had roughly twenty miles to cover to reach our shuttle car, and even dusty roads and flat terrain felt punishing. Finishing the route this way was still beautiful, but we’d love to return someday to summit Mount Stewart and mentally stitch the route together as originally envisioned.

The final five miles to the car were brutal. What began as a relaxed “staycation” in a new range had evolved into a four-day epic we won’t soon forget. Still, neither of us regretted giving it a shot. Seeing the entire Salt River Range in such a compact format was deeply satisfying, and the experience felt earned in every sense.

Would we do things differently if we went back? Absolutely. But it will take many years and a fair amount of forgetfulness before we willingly sign up for that scree-filled maze again. The Salt River Range Traverse is a worthy long-weekend adventure, but pack your ibuprofen and your resolve. It’s a long, rugged ride.