Teton Endurance Triathlons

Around the Clock Triathlon (FA 2015)

Picnic (Grand Teton Triathlon-PR 11:25)

Grand, Middle, South Picnic with Kelly Halpin (FA 2017)

Cathedral Traverse Picnic with Lewis Smirl (FA 2024)

Grand Traverse Picnic (FA 2019)

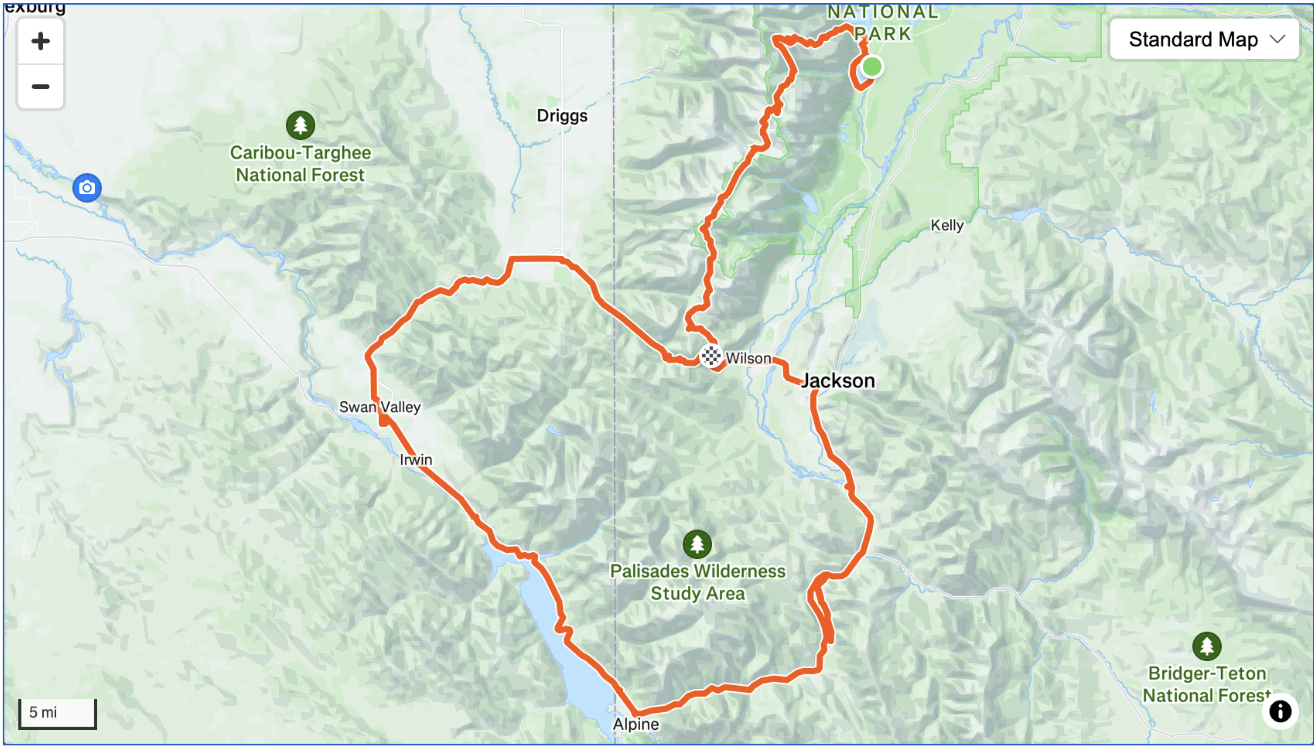

Around the Clock Triathlon

Triathlon Background: The previous summer, I’d finished the Picnic Triathlon and felt like I still had energy left in the tank. I wanted something that would push me to my absolute limit — a challenge that left no doubt about what I was capable of. Since I was only going to be young once, I figured I should exhaust myself fully at least once in life. This triathlon was my quest to go all in — and it didn’t disappoint.

I remembered a documentary about the first Ironman Triathlon, where the founders simply combined the three hardest endurance events on the Big Island of Hawaii into one race. I loved that concept. So, I decided to take the hardest swimming, running, and biking objectives I could think of near Jackson Hole and merge them into a single, massive day. Maybe not the absolute hardest — the routes had to be close enough together — but still a serious undertaking:

At the time, I was working as a substance abuse counselor and only had weekends off. I taught a DUI class until noon on Saturday and entered the water by 1:30 that afternoon — beginning what would become a 30-hour journey that ended at Teton Pass on Sunday night. I hadn’t slept the entire time and still logged into work bright and early Monday morning.

1st leg of the triathlon is swimming around the perimeter of Jenny Lake

The Swim

Before starting the swim, I was intimidated by the distance. I had only ever swam about 1.5 miles in one go, but I remembered reading about an older gentleman who had swam over 65 miles across the English Channel — freezing water, strong currents, and all. Compared to that, my challenge seemed tame.

My rationalization was simple: if it got too hard, I’d just get out. At least I’d tried.

Surprisingly, the swim wasn’t half as bad as I imagined — it turned into a stunning journey through the underwater world of Jenny Lake. I had no idea there was so much to see down there. Algae-covered logs, ancient-looking rocks, and eerie depths made it feel like traveling back to the Jurassic Era.

For six hours, I alternated my gaze between the towering peaks above and the mysterious landscape below — a strange meditation on two contrasting worlds, both magnificent in their own ways. I did get cold at times, especially when the clouds rolled in and my thin wetsuit lost its warmth. The second half of the swim was mostly me cursing myself for being too cheap to buy thicker neoprene. But I was a skid at the time and couldn’t justify the expense.

When I finally reached shore, I had to crawl out of the water — my legs were useless from the cold and repetitive motion. Somehow, I peeled off the wetsuit and shivered my way back to life after ten minutes or so.

At that point, it would have been great to have a support crew, but I always feel guilty asking anyone to give up a weekend for one of my ridiculous athletic indulgences. I was back at my car, and the thought of driving into town for a hot meal definitely crossed my mind. But I knew I’d never want to swim that far again, so it was now or never.

2nd leg of the triathlon runs along the Teton Crest Trail

The Run

Starting up Paintbrush Canyon, I was just happy to be on dry land. My confidence was high — until the sun went down and the animals came out.

I had headphones and a Taylor Swift playlist to keep me company, so I sang “Blank Space” for most of the night to alert the bears of my presence. Normally, bears in the Tetons don’t scare me, but running through the dark at a decent clip unlocked some new fears.

The 42-mile run was otherwise uneventful — no great views at night — but it was oddly satisfying to pass sleeping hikers under the stars. I only got lost once in Alaska Basin, where the trail fades among the rock slabs. The sun rose somewhere around Phillips Pass, giving me a much-needed boost for the bike ride ahead.

3rd leg of the triathon passes by Palisades Reservoir in Alpine, Wyoming

The Bike

I’d left my road bike at Phillips Bench the day before, chained to a tree with a food resupply next to it. Thankfully, it was still there, patiently waiting.

In my head, the 108-mile bike ride would be tedious but doable. My mantra: “Just let the bike do the work.” That worked for the descent down Teton Pass, but the climb over Pine Creek Pass was brutal.

I kept myself moving with thoughts of Pop-Tarts and Coca-Cola from the Swan Valley store twenty miles ahead — a sugar combo I’d never craved before, but apparently that’s what my body wanted. Somehow, I made it to Alpine and began the long push back toward Jackson.

Things got blurry here, but I remember the first flat tire in Hoback, and the second just outside of Jackson. I had one patch kit but no spare tube, so I swapped bikes at my house on East Kelly Street and finished the last twenty miles on my mountain bike.

That would’ve been fine — except for the small detail of ending a 30-hour triathlon with a bike up Teton Pass. I made it most of the way, but the last half mile broke me. I dismounted and pushed that hunk of metal to the finish line.

When I finally reached the top, I could’ve ridden my bike down to Wilson — but choose instead to hitch a ride back into town. My body refused to exercise for for even one more second.

Triathlon Notes

Swim: Started at Jenny Lake Overlook, swam clockwise around the lake.

Transition: Kept food resupply and running gear in my car.

Run: Went light, but brought a down jacket for warmth (highly recommended).

Bike: Left road bike and food stash in a bear canister at Phillips Bench.

Pro tip: bring panniers so you’re not carrying weight on your back.

Bring multiple patch kits — learn from my mistake.

This was an amazing tour of the Teton Range — part suffering, part serenity, and all adventure. Just do it!

The Around the Clock Triathlon was featured in the JH News and Guide and JH Style Magazine

Jackson Hole Ironman

First Triathlon Race Day: College Senior Year with Liz Butler

JH Ironman Background: During my senior year of college, I completed my first triathlon. I still vividly remember standing in the staging area, feeling an unexpected surge of envy toward an older gentleman wearing an Ironman finisher race kit. I had no idea how long it took him to complete the race or where he placed. None of that mattered. He had finished. That alone felt like the ultimate flex, and it was working. I wanted to be him. At that point in my athletic journey, a 10K was my comfort zone. The idea of stringing together a marathon, 112 miles on a bike, and a 2.4-mile swim felt borderline torturous. His accomplishment seemed impossibly distant, yet deeply admirable. He wore that shirt like it carried a story, and it did. Who could blame him? Finishing an Ironman is a tremendous achievement. I remember quietly thinking that if I ever earned the right to wear that shirt, I might never take it off.

That moment planted a seed, though it took another eight years of incremental progress before the idea of standing on an Ironman start line felt remotely reasonable. I credit much of that shift to the Jackson Hole lifestyle. Living here has a way of breeding confidence. You begin in awe of the Tetons from the valley floor, and over time, you inch closer. First, a hike to Amphitheater Lake. Then a non-technical climb up the Middle Teton. Eventually, with equal parts fear and resolve, you find yourself standing on the summit of the Grand Teton. Each step carries its own anxiety and reward, yet there is always another challenge waiting. That’s the quiet magic of this place. It teaches you to believe in yourself. You see a challenge, you meet it, and then you look ahead to the next one. Over and over again, the cycle continues.

Living in Jackson does come with its downsides. One of the more obvious ones is that the cost of living tends to leave the wallet a little thin. The entry fee for the Ironman in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho — the closest race to me at the time — was around $450. For a ski bum in Jackson, that felt like a steep price to pay for voluntarily suffering all day. I tried not to let the number deter me, but I couldn’t quite justify traveling a fair distance, spending a lot of money, and enduring a massive physical ordeal just to earn a T-shirt and, maybe, a modest bump in status.

That’s when it clicked. The Ironman logo splashed across my chest wasn’t actually what I cared about. What I was after was the feeling that comes from covering that distance — the quiet satisfaction of seeing something hard through to the end. Once I let go of the symbol, the solution became obvious. Instead of paying for an Ironman, I would create one of my own, starting right out the back door.

Cross Country Bike Ride with friends Brian Alward and Travis Rave

At that point in my life, I hadn’t designed an adventure of this scale on my own, so my choice of venues was admittedly a bit uninspired. In hindsight, I wish I’d selected three locations with a little more pizzazz, but I was new to the game and only just beginning what would become a decades-long habit of creating slightly wacky personal adventures. My limited imagination was also paired with a very practical concern: I had no interest in spending a few hundred dollars on a wetsuit just to swim in one of the frigid alpine lakes around Jackson. That narrowed my options considerably. In the end, I completed the 2.4-mile swim in the local rec center pool. Not exactly an open-water epic, but it felt like a comfortable way to dip my toes into the shallow end of a much bigger endeavor.

I’m not someone who typically trains for objectives, but I had never swam that distance before, so I logged a few long pool sessions simply to make sure I didn’t accidentally drown. Once I got going, things flowed surprisingly well. Swimming has a meditative quality, and the distance passed more quickly than I expected. A big part of the appeal of a traditional Ironman is the camaraderie — being surrounded by others chasing the same goal. But there’s also something uniquely powerful about tackling an objective alone. The main benefit is simple: you’re never slower than anyone else, because there is no one else. I also appreciated how it forced me to keep going even though no one knew what I was doing. I’ve grown to enjoy race environments, but for these kinds of self-designed adventures, my real aim is mental expansion. And that tends to happen faster when I’m by myself.

Next up was the bike ride, which I completed on an ancient mountain bike I had previously ridden across the country right after graduating college. My logic was simple: if it could survive 20 states, it could survive 112 miles. I was broke at the time, and my budget didn’t allow for upgrades. I might have swapped out the studded tires for something more road-friendly, but given that my total race budget hovered around twenty dollars, that seems optimistic. Undeterred by the bike’s limitations, I rolled out of downtown Jackson and headed 65 miles south toward Thayne, Wyoming, my turnaround point. That stretch of the day is largely unmemorable, aside from my sit bones loudly protesting the lack of preparation. Fueled by Pop-Tarts and Coca-Cola, I reached Thayne, turned around, and began the long ride back toward the final leg. The route through Hoback Canyon was beautiful, though I was far too preoccupied with the fear of mechanical failure to fully appreciate it.

Half Ironman Training Run in Maine with my brother Christian and friend Molly Gove

Waiting for me at the end of the ride was my girlfriend, Lindsay Goldring, and my bright blue Ford Explorer Sport. I was genuinely happy to see both, though the temptation to call it a day and go grab a drink was strong. Instead, I laced up for the run: a planned out-and-back to Teton Village, entirely on pavement. Living in Jackson, I almost exclusively run trails, and my knees have long thanked me for that decision. Looking back, it’s baffling that I willingly chose to spend 26.1 miles pounding pavement. I think I wanted something flat and predictable, but I paid dearly for every step. Lindsay biked alongside me for part of the run, which helped keep me moving, but once she peeled off to pick up her dog, the remaining miles felt significantly heavier.

I remember feeling a vague sense of euphoria in the final miles, though it wasn’t joy so much as the relief you feel when a crying baby finally settles down. It’s strange to think that this day marked the beginning of my endurance athlete phase. I’m still not entirely sure what I liked about it, but I knew that I did. Objectives like this are odd in that way. No one can fully explain why they’re drawn to them. You can dress it up with language that sounds plausible or even poetic, but the reality is that this kind of effort doesn’t make much sense. You’re subjecting your body to something brutally demanding with no clear evolutionary benefit. No one is handing out food, shelter, or security at the finish line. If someone had asked why I did it, I might have joked about earning the right to wear a finisher’s shirt around town. But there was no shirt waiting for me. What was left, instead, was quieter and harder to name: the satisfaction of discovering that I could endure more than I thought, even when no one was watching and nothing tangible was promised in return.